Why one Texas farmer is betting big on cattle as drought, weak markets and high input costs reshape the plains.

It begins on a wind-burned stretch of Floyd County, where the soil has carried four generations of the Smith family through seasons that were generous, seasons that were tight and seasons that tested a rancher’s faith more than the weather ever could.

For Eric Smith, tradition is not a business plan. Survival is. And survival today means thinking differently about every acre he farms.

Right now, survival looks a whole lot more like cattle and a whole lot less like row crops.

The Man Who Won’t Farm on Autopilot

Smith does not farm the way his father did. He farms the way the times demand

The Smiths always kept stockers in their operation, but the last few years forced a major shift. More hooves, fewer rows and a stronger focus on business flexibility. And with his oldest son Ethan home from college and ready to step in, the family is expanding the herd.

When the Water Runs Short

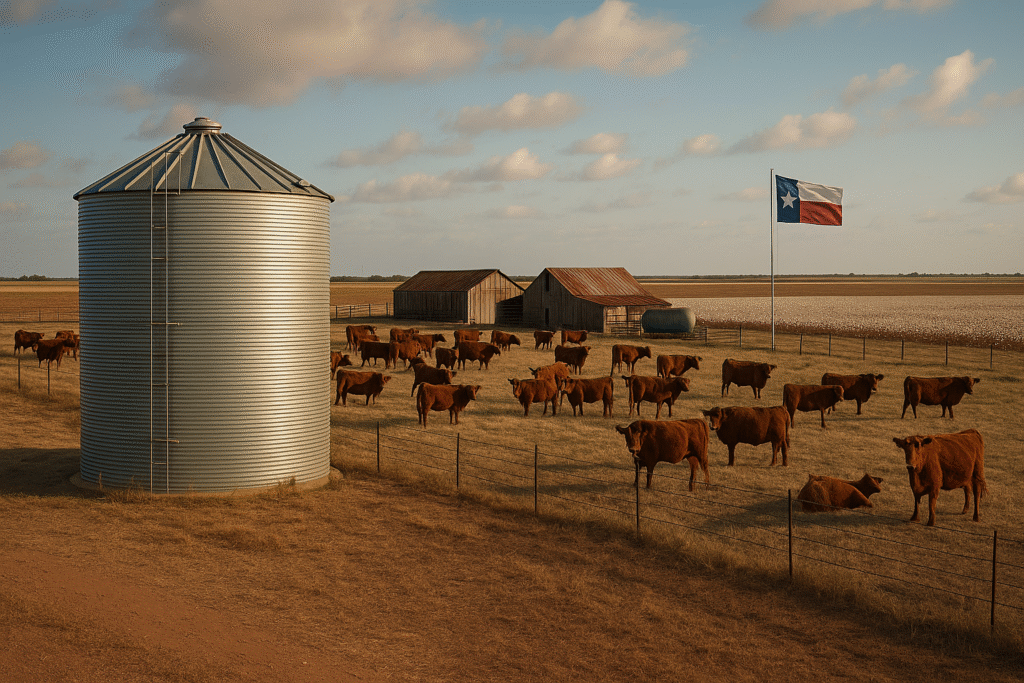

The biggest change is not personal. It is physical. Since the year 2000, Smith’s irrigation capacity has fallen by about 35 percent. That is not a minor adjustment. That is a new reality, carved out one dry year at a time.

“We are cutting back on cotton acres because of our water restrictions,” he says. Out on the High Plains, the aquifer has more authority than any man. When it drops, everyone pays attention.

When Costs Climb and Prices Sink

Cotton once felt predictable. Today it barely covers the bills. Input costs have risen across the board. Fuel, fertilizer, chemicals and seed all ask more from the grower. Smith also sees a pattern that is hard to ignore.

“We get support from the government, and the minute that happens, input prices seem to climb with it,” he says. “It gets tough to stay ahead of the curve.”

So he and Ethan spend more time studying numbers and less time relying on what used to work

A Rotation Built to Survive

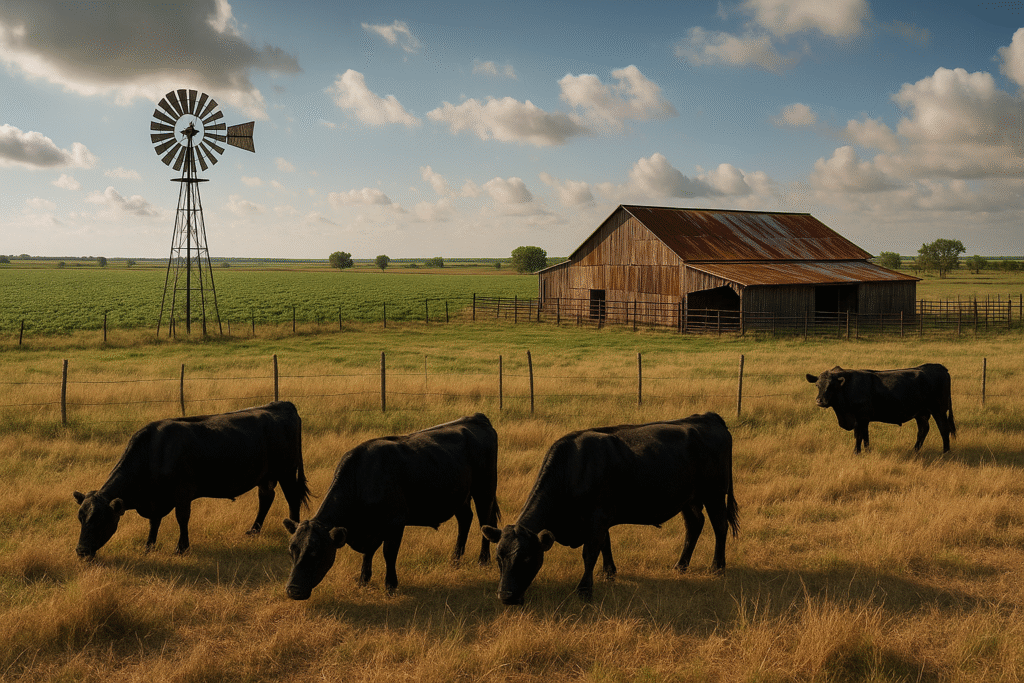

Their rotation is wide and carefully planned. Cotton, wheat, oats, millet and grain sorghum create options for grazing and forage. The cattle sit in the center of it all.

“The cattle fit into everything we are doing,” Smith says. “We try to make every acre work for something.”

Diversification spreads risk. It also stretches the workload across the entire calendar.

“My wife and I used to talk about slow seasons,” he says. “We do not have slow seasons anymore.”

Harvest cotton. Drill wheat. Receive cattle. Sort cattle. Ship cattle. Repeat. Operations cannot afford downtime. They need revenue moving in constantly.

A Stocker Market on Fire

It is keeping prices very high,” Smith says. “Good if you are selling. Tough if you are buying

Says farmer Smith

Record cattle prices sound like relief, but the reality is more complicated.

“With the southern border closed and the screwworm problem, the supply of cattle is tight,” Smith explains. The numbers tell the story. In 2024, the United States imported 1.25 million head worth more than 1.3 billion dollars from Mexico. Since July 2025, not a single head has crossed.

The result is a pipeline that feels thin. Fewer cattle to buy and more competition for what is available. Great news for sellers, but a challenge for everyone trying to build or maintain a stocker program.

Producers who once relied on wheat for grain are now planting wheat for grazing. That shift increases demand for cattle even more. Tight supply meets strong demand, and prices climb.

Looking Toward 2026

Smith sees his path clearly. More cattle. Fewer cotton acres. Maximum return per dollar spent.

“We may cut back on cotton acres again,” he says. “We are concentrating our resources where they earn the most.”

No nostalgia. No guesswork. Just a constant adjustment to a moving target.

The land changes. The markets change. The water changes.

To survive, a farmer changes with it.

And in Floyd County, the land always has the final say..